Dashi and

Umami –

The Essence of

Japanese Cuisine

Although Japanese cuisine is rich in diversity and visually attractive, there is one element underlying its appeal that is not apparent to the eye. This is a deceptively simple element called “dashi,” the stock that forms the basis of, and invisibly permeates much of, Japanese cuisine.

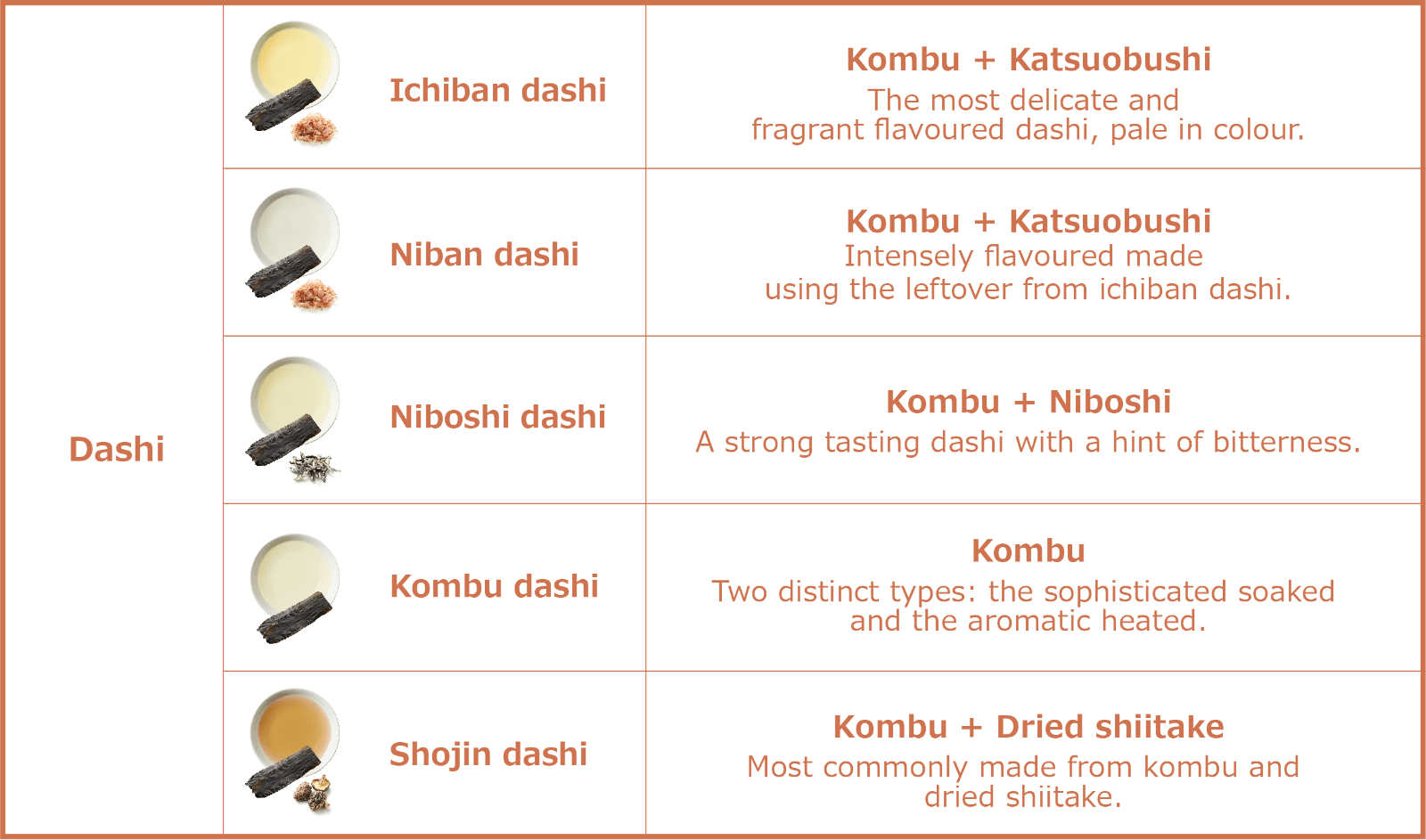

Dashi differs from other kinds of stock in that rather than using simple ingredients boiled over a long period, as is the case with Western bouillon, it uses carefully prepared ingredients, patiently matured, which are only soaked in water or heated briefly so as to extract nothing but the very essence of the ingredients’ flavor.

Dashi most commonly utilizes a combination of kombu (kelp seaweed) and katsuobushi (dried bonito flakes), but other ingredients used to make dashi are shiitake mushrooms and niboshi (small dried fish). Dashi making has evolved over a long period of time. Boiling is known to have been used in Japanese cooking since the Jomon period (c. 13,000–300 BC), and the stock from shellfish and fish bones was used to flavor other dishes.

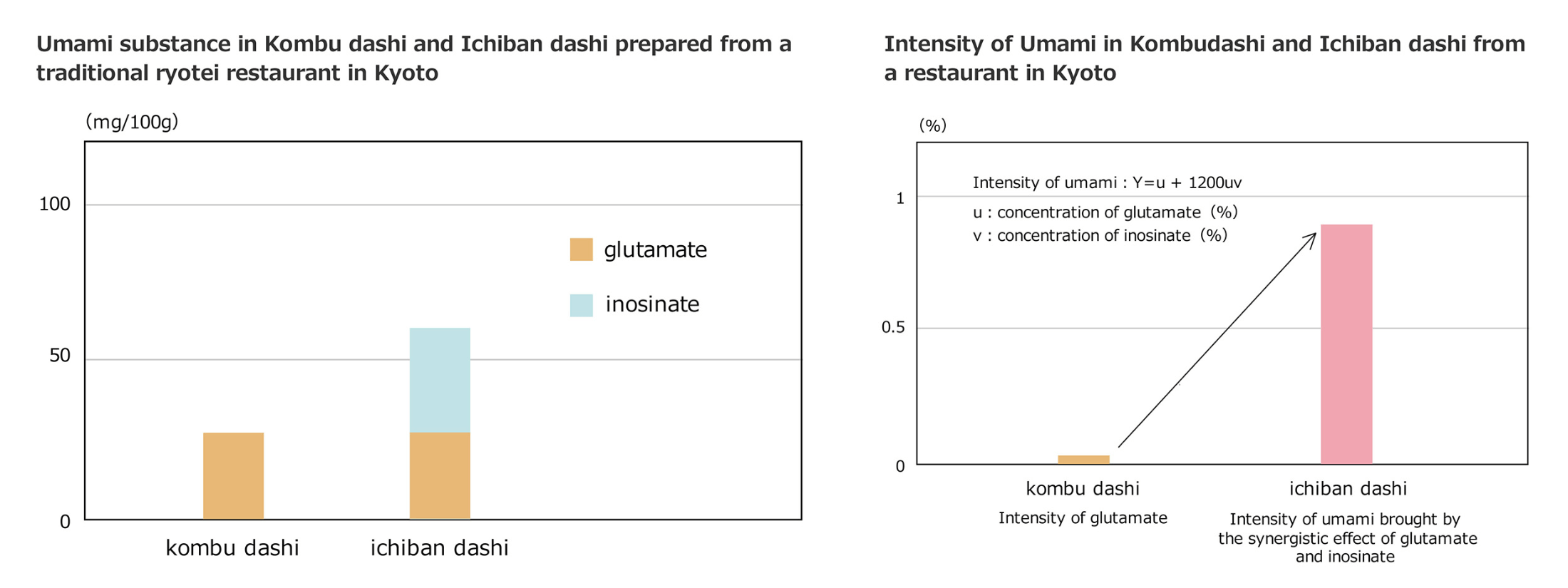

By the seventh century, a dashi using kombu and katsuobushi had developed. This was refined further and has become Japan’s most indispensable cooking stock, generally used in two forms – ichiban (primary) dashi and niban (secondary) dashi. Despite its hidden role, dashi could be said to be the heart of Japanese cuisine, not because of the prominence of its own flavor but because of the way it enhances and harmonizes the flavors of other ingredients. The secret of Japanese cuisine is the art of enhancing and harmonizing.